By age 14, I had pieced together my sexual knowledge using a heavy-handed Catholic lecture on abstinence in Sunday school, a year-long “health” class my first year of high school and a plethora of teen drama television shows. I had extensive knowledge of the graphic effects of certain sexually transmitted diseases on penises, I had seen a condom put on a banana at least two times and had heard of, but could not fully understand, a dental dam. The topic of consent, however, was left mostly untouched.

When I received the Project SAFE orientation training four years ago, the language surrounding consent, and even the term “affirmative consent,” were entirely unfamiliar to me. As an 18 year old, I wondered why I hadn’t learned this information earlier and how differently so many of my sexual encounters would have gone if I had known how to assert my boundaries and vocalize my needs.

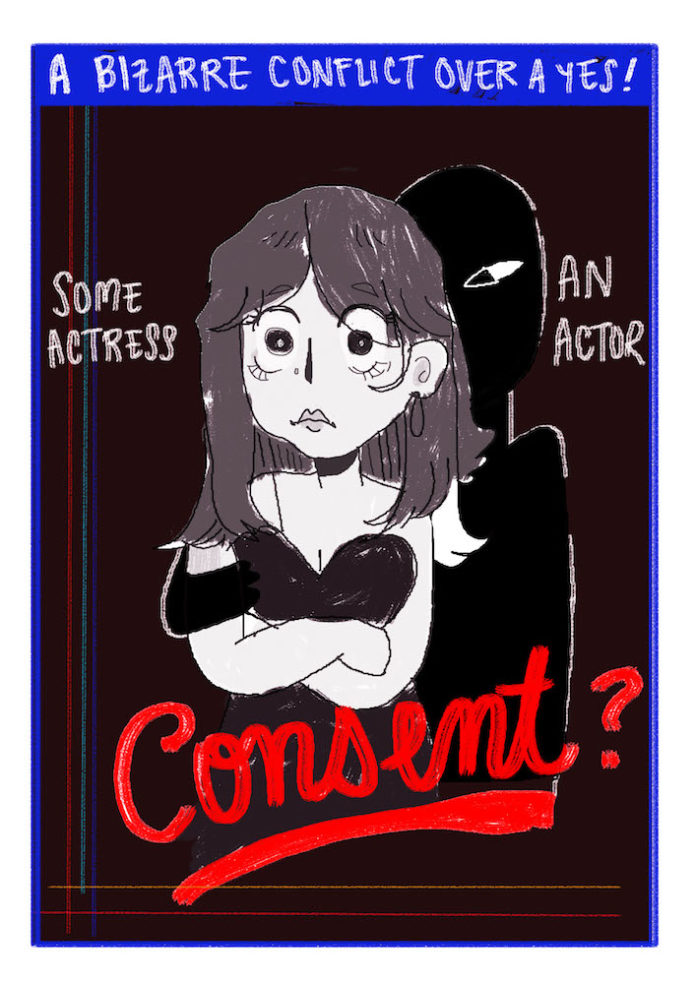

Affirmative consent, as defined by California legislation, means that the consent must be ongoing, reciprocal, mutually understandable and freely given in order for a sexual encounter to be consensual. Consent is not just communicated through a verbal “yes” — it’s communicated through open body language and questions about what the other person likes. Knowing how to communicate consent allows us to address and understand our own boundaries and desires. Even more, it opens us up to a world of communication because it gives us the tools to engage in healthy, equitable and pleasurable sexual encounters. Consent can be complex and awkward, but ultimately it’s the basis of any mutual sexual encounter, and it draws a clear line between sex and sexual assault.

Now, as a 21 year old, my own personal experiences and my role as a Project SAFE Programming Assistant (PA) have reworked my understanding of consent. As a PA, a big part of my job is talking about consent in front of big groups of other college students. In these conversations, I’ve found that we’re oftentimes unsure of how to talk about consent in an honest way. Looking at the lack of knowledge we receive from high school sex ed and society, it makes sense that we’re uncomfortable talking about consent.

As an only child, movies, television and Google were my best friends (and also my worst enemies) when figuring out what everything sex-related actually meant and what everyone was actually talking about. I identified with characters, emotionally attached myself to them and compared my own life trajectory with theirs. But looking back, I realize that nearly every show I watched barely, if ever, acknowledged consent in a satisfactory manner. Studies show that providing clear, unambiguous representations of consent in sexual situations is critical for giving viewers, especially younger ones, an understanding of consent.

For example, in “Gossip Girl,” a highly-viewed teen drama based on the intimate secrets of an elite, Upper Eastside high school clique, the characters have plenty of sex. Often, the question of consent is washed out by the scandalous and salacious nature of the sex. Chuck Bass, the primary love interest of main character Blair Waldorf, attempts to assault two of the other main characters within the first three episodes of the first season. But after that, the other characters’ memories of the assaults disappear completely. By overwriting these violations of consent, the show writers are falsely telling viewers that violating consent is not a serious issue.

We need more accurate representations of affirmative consent in media and television in order to emphasize its importance and ease the discomfort we feel when talking about it. Even further, we need consent in television that is neither ambiguous nor heteronormative, as these representations only perpetuate deeply ingrained power dynamics between men and women — and completely exclude LGBTQ+ folks. By ignoring the reality of consent and sex, media is doing us all a disservice and leaving us with unrealistic expectations. Having more representations of consent in media would give us the rhetoric we need to better understand consent and how to advocate for ourselves.

There’s still hope for depictions of consent on television, though. At the moment, my favorite example of healthy consent communication is Netflix’s first season of “Sex Education,” a show in which characters grapple with their burgeoning sexualities. We see high-schoolers communicate their consent, preferences, boundaries and triggers in wonderfully awkward and real ways. By leaving in the realistic in-between moments, “Sex Education” shows us that sex is sometimes uncomfortable and always vulnerable.

Consent facilitates an open level of communication that serves the rest of the sexual encounter well, too. Sex is a lot better when we’re actually talking about it, from the positions we like to the places where we like to be kissed. Like consent, I think sex can be intimate or awkward, but at its core, it is incredibly vulnerable. Leaning into consent’s vulnerability has taught me to vocalize my boundaries, be more cognizant of my partner’s boundaries and be more honest through it all.

Emma Robitaille is a senior Media Arts & Culture and Spanish double major. She can be reached at erobitaille@oxy.edu.

![]()