It’s Feb. 24, and Oxy Confessions just posted for the first time in a month.

Obsessively checking for updates, speculating about the moderator’s identity and anonymously complaining about those monsters who dare eat chips in the quiet section have all become Oxy rituals since the page’s creation in 2013. For many, Oxy Confessions’ revival after a long period of silence may seem like a welcome return to normalcy — finally, we can get back to yelling at each other on the internet again.

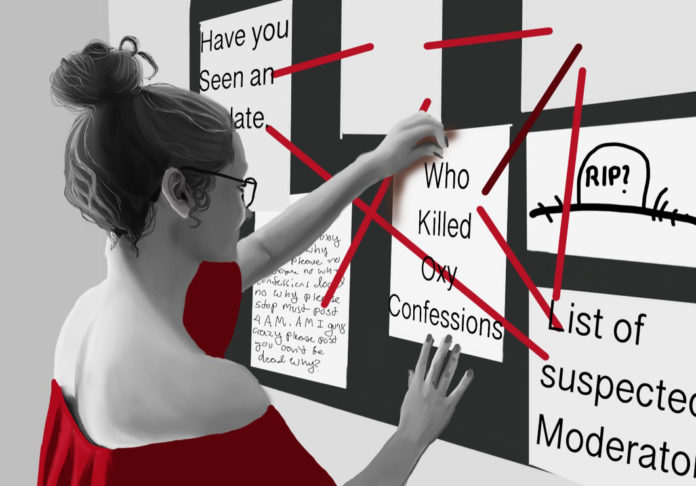

But I moderated the page for about six months last school year, so let me burst your bubble with an insider’s wisdom: Oxy Confessions is a dumpster fire of a website, and we need to let it die. The page just isn’t structured to be efficiently or healthily run by one person. In fact, it’s not structured at all.

Let’s step into the shoes of junior-year me. Here you are in the shoebox charitably called a Stearns single, sitting at your computer. You’ve got a paper due, office hours to go to, readings to finish. But all of that has to wait; you haven’t posted on Oxy Confessions in four days, and the mean messages are starting to come in. You’re not going anywhere for the next hour. You have to tackle The Spreadsheet.

The Spreadsheet is where your unpublished Oxy Confessions go to die. It’s a Google Sheet that automatically logs each submission from the Google Form on Oxy Confessions’ main page, and it is a vast, horrifying look into Oxy students’ collective id, rapidly yo-yoing between inanity and insanity. My task was to sort through the mess, find confessions worth posting, number them and copy and paste them onto Facebook one by one. It’s inefficient, it’s time-consuming — and it’s the least terrible part of the process.

The first major problem arises from the fact that Oxy Confessions has no official rules (a trait I once praised in my innocent pre-mod days). Behind the scenes, it has five: no blatant argument bait, no targeting specific students, no overtly sexual comments, no advertisements — and when in doubt, don’t post it. My predecessor passed these rules on to me, but advised me not to post them publicly. There was too much gray area. Iffy posts would inevitably come in that didn’t technically break any rules, and people would inevitably get upset when they didn’t appear on the page.

But there was plenty of gray area within the rules, too. Out of all the angry political confessions, which counted as bait? Was “thicc” a sexual word? Was it targeting to call out the person loudly skateboarding outside Berkus? Some confessions — accusing others of sexual assault, detailing suicidal feelings or telling other hyper-specific personal stories — I had no guidelines for at all. Week after week, I felt like I was trying to put a leash on a fish. The simple, secret rules weren’t enough to even encompass, much less control, every thought Oxy students decided to share.

We already know from previous op-eds (and common sense) that the anonymity of Oxy Confessions allows its posters to dodge accountability for their views. But as the only person unhappy readers could contact, I became a proxy for the person they were actually arguing with. Often, I got messages trying to pick a fight over views I didn’t even share, or demanding I take down posts because the reader didn’t agree. Of course, sometimes my eyes would glaze over while sorting through The Spreadsheet and I’d accidentally let something nasty slip through the cracks; in that case, I’d quickly take it down. But most of these posts weren’t like that. Controversial submitters had the luxury to start a fight, then dip, but my phone never stopped buzzing from the fallout. If I tried to avoid conflict by scaling back on the political posts, in came the angry messages from the people who had sent them.

Like a frog slowly boiled alive, my mental health suffered without my noticing. I constantly felt paranoid, simultaneously invisible and hyper-visible. I worried everyone would hate me if they found out I was the mod. I worried everyone secretly did know I was the mod and already hated me. I didn’t have the time to sort through The Spreadsheet every three days, and I didn’t have the mental energy to defend myself from the onslaught when I put it off. I was constantly calling my mom crying from the stress, and though she kept telling me to just pass it off to someone else, I felt like I couldn’t. I remembered how excited I’d been when my predecessor accepted my offer to take over. Moderating Oxy Confessions was supposed to be an honor. I was supposed to be having fun.

Eventually, I took my mom’s advice, and a weight lifted.

I know I risk coming across as dramatic, so let me be clear: the anonymity, disorganization and solitude were really what made Oxy Confessions so hellish. I loved my year as an opinions editor here at the newspaper, which, like moderating Oxy Confessions, entailed sharing opinions I didn’t necessarily agree with. But those opinions had to be argued clearly and backed up with evidence and a byline, and I could offer my own input to help make them stronger. If they made readers unhappy, we could sit down together and talk it out, and those readers would often write a counter-op-ed to share their own perspective. It felt like an ongoing conversation — never an endless fight.

Our views, ideas and stories are valuable, and they deserve a better home than an anonymous Facebook page. Oxy Confessions has had a good run. Let’s leave it in the past.

Natalie Ray is a senior English major. She can be reached at nray@oxy.edu.

![]()