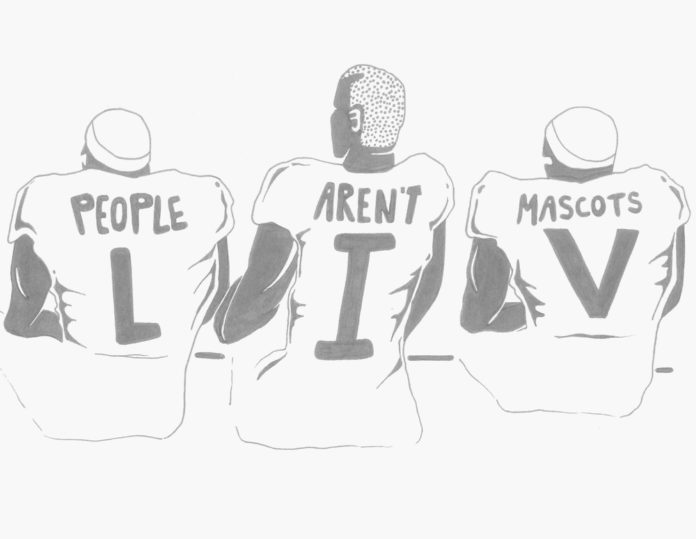

The conclusion of last Sunday’s Super Bowl added another ember to the fiery debate over the cultural appropriation of Native Americans. As I watched the red and yellow confetti rain down over the victorious Kansas City Chiefs, I was confronted with the problematic history Native American mascots evoke: that of an entire community of people diminished to a caricature. Seminole and Sioux activist Michael Haney told the Chicago Tribune in 1993 that “as long as white America feels that Indians are not quite human, that we can be construed as mascots or caricatures or cartoon figures, then they will never deal with the issues of education and economic development for our people.”

Though coaches and staff from the Kansas City Chiefs have been meeting with local tribes to discuss the implications of the Chief mascot for the past six years, the effort has only resulted in “meaningful dialogue” and no change. The Chiefs, who got their name from a white man who impersonated a Native American, represent a broader reluctance to acknowledge the oppressive nature of American history and traditions. It frames appropriation as “respect.” The idea that using a Native mascot constitutes respect perpetuates the deeply-rooted falsehood that this country was not founded on stolen land and violent colonization and instead, as I learned in elementary school, through fair land trades and amicable gatherings like Thanksgiving. Thus, Native American mascots and subsequent caricatured imagery validate damaging tropes that are deeply ingrained in colonial history of Native Americans as savage, uncivilized, lesser beings.

The contours of the problem are far too recognizable. Native communities and allies call for the removal of the caricatured, offensive mascots while groups of non-Native, often white, fans demand to keep them for the sake of “tradition.” The National Congress of American Indians has been campaigning to eliminate these team names since 1968 — an effort that has resulted in tens of high schools and universities removing Native American mascots. Yet on a national level, these damaging mascots persist. Take, for example, the Washington Redsk*ns, a national football team that has pushed harmful imagery and rhetoric about Native communities since adopting the name in 1933. Merriam-Webster recognized Redsk*n as a derogatory term in 1898, and it’s inarguably still considered a slur today. But in a letter to Congress in 2013 defending the use of the word, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell declared that Washington’s name was “a unifying force that stands for strength, courage, pride and respect.”

Goodell’s warped understanding of respect has no scientific or psychological backing. Studies show that these mascots facilitate stereotypical, harmful notions of Native Americans and negatively impact young Native Americans’ self-perception. Accordingly, the American Psychological Association called to eliminate the use of Native American mascots in 2005. Essentially, these studies prove what is intuitive: racism and discrimination have highly damaging effects on emotional and psychological health.

These names remain normalized on a more local, personal level in high schools across the country. I attended an affluent private school in Southwest Ohio, nestled in a neighborhood known as Indian Hill, where my school’s mascot was the “Indians,” a reference to the Shawnee tribe who were forced from their land nearly two centuries ago as a result of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830. For the most part, there was little to no dialogue or interrogation of the mascot at my school. Every so often, students wrote opinion pieces on whether or not we should maintain the name, usually including comments from other students, many of whom were white, on why the name should be kept. Even in 2014, our Homecoming pep rallies still featured a mock “battle” showcasing a student clad in a headdress and Native costume beating our rival with a plastic ax. Perpetuating and actively enforcing inaccurate stereotypes is a twisted way of honoring a tribe that was forcibly removed from their land.

Most high schools in my surrounding area also had equally unoriginal and offensive names. Down the street were the Braves, and a few counties over, the Redsk*ns. In 2018, the Branding and Mascot Committee for the Redsk*ns recommended the school keep the name after a long-winded and heated debate. Supporters of the name sported “Once a Redsk*n, always a Redsk*n” T-shirts and started a Change.org petition to make their voices heard — 3,535 people signed the petition to preserve the name. The push to change the name still persists, and in September 2019, graffiti criticizing the name appeared on the athletic track and dugout.

By preserving and playing to inaccurate stereotypes, we are complacent in erasing the contemporary, and very real, identity of Native Americans. If the intention is to honor indigenous communities, we would be better served to counter our discovery narratives, acknowledge the trauma of colonization and interrogate the images that saturate our culture. This would entail more than just meaningful dialogue — it would call for, among many other things, donating to native organizations, honoring native land and changing the names of sports teams.

Emma Robitaille is a senior Media Arts & Culture and Spanish double major. She can be reached at erobitaille@oxy.edu.

![]()