Woody Studenmund arrived in California in the fall of 1970 with a broken leg and a fever of 102. He had no luggage, no car and no place to live. All signs pointed to a sojourn that would last a few years at most.

“I assumed, being a New Yorker, that I’d just come right back again after three years,” Studenmund said.

His prediction was slightly off. Last year marked Studenmund’s 50th as an Occidental College professor — he is tied for the longest-serving faculty member with English professor Jean Wyatt, who joined the same year.

As the school’s Laurence de Rycke Professor of Economics, Studenmund has witnessed the coming and going of eight Occidental presidents and served in a variety of administrative roles under several of them. More recently, Studenmund has become the inaugural faculty adviser to Occidental’s Veteran’s Programs initiative, a role he assumed in the years following his son’s service and death in Afghanistan.

He is also the author of the primary econometrics textbook of use at liberal arts colleges, which has gone through seven editions.

“Woody wrote the textbook,” said Emily Davis (senior), one of Studenmund’s advisees, emphasizing “the.”

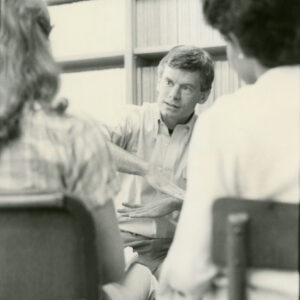

Yet, teaching is the reason Studenmund has remained at Occidental. Studenmund said he most enjoys the opportunity to help students achieve their goals.

“Isn’t that what college is all about?” Studenmund said.

‘A logical mind’

Studenmund grew up the eldest of four siblings in Cresskill, NJ, the son of a teacher and a businessman. However, Studenmund was born and spent the majority of his summers in Cooperstown, NY — the home of the Hall of Fame for the sport which would become one of Studenmund’s life passions: baseball.

“Two doors down was the director of the Hall of Fame. He didn’t mind if he got a baseball in his backyard,” Studenmund said. “I played baseball on Doubleday Field every afternoon, pretty much every summer.”

Foreshadowing the interest which would lead him into economics, Studenmund began to play American Professional Baseball Association, commonly known as APBA, a board game based on annual baseball team and player stats. In 1967, he founded the North East League, the oldest still-running mail-in league for the simulation sport. Studenmund’s affinity for baseball rubbed off on his younger brother of 10 years Dave Studenmund, who attributed his love for the sport to Studenmund and said that he grew up idolizing him.

“We all have a memory of the dice rolling,” Dave said. “He’s a very logical mind and baseball is a very logical sport.”

‘Are you going to Oxy?’

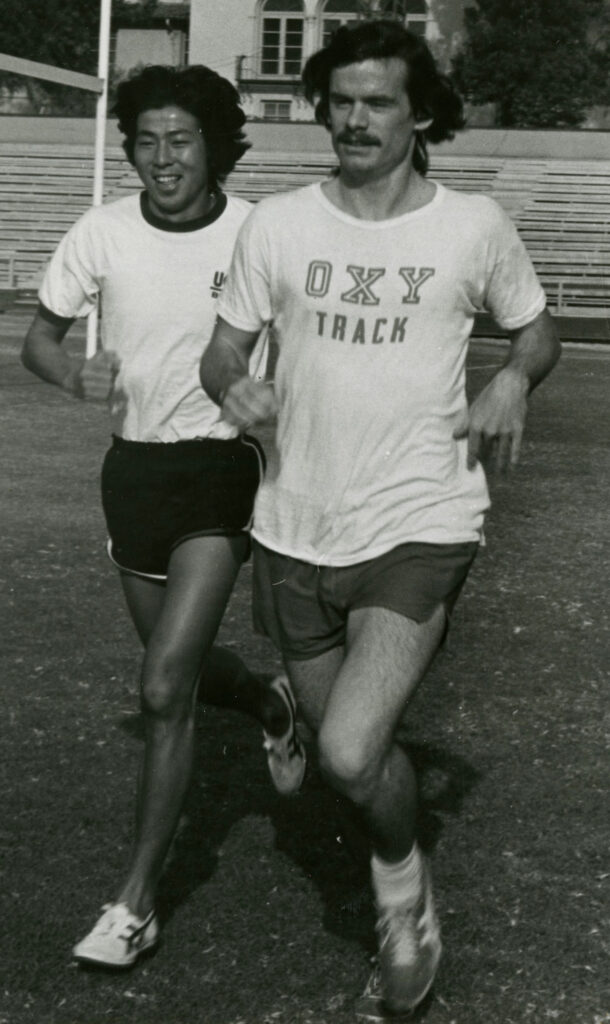

Studenmund returned to upstate New York as a college student, earning his Bachelor’s at Hamilton College in 1966 and his Ph.D. in economics from Cornell University in 1970. He ran track and sang in choirs and experienced the tumult of life as a college student amid the 1960s civil rights and anti-war movements.

“It certainly was a radicalizing time for me,” Studenmund said. “It made you think about values, made you think about fairness.”

Studenmund said he liked Cornell but was not satisfied with the university’s focus of the economics teaching: too much theory, not enough application.

“I truly believe that the best way to prepare informed citizens is a liberal arts education,” Studenmund said. “So I very much wanted to teach in a liberal arts place rather than teaching a place that focused on research or proofs.”

The promise of better weather in a place like LA did not hurt, and Dave said he remembered a California poster hanging in his brother’s apartment the year before Studenmund moved out west. Offered a position in Occidental’s economics department, Studenmund jumped on it.

Studenmund touched down in LA at the age of 25, bringing with him his fever, his broken leg and his youthful anticipation. There was no direct bus from the airport to Occidental, so he boarded one to Pasadena.

“And when I got at the bottom of the bus ramp, someone said to me, ‘Are you going to Oxy?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And he drove me there,” Studenmund said.

That man was Dave McMenamin ‘69, the son of former biology professor John McMenamin ‘40 and former alumni relations director Addie McMenamin ‘40, who would work at Occidental for a combined 56 years between them. After their chance encounter, Studenmund lived with the McMenamins for several weeks and became a mainstay at their Thanksgivings for years to come.

“One of the things I set out to do was to try to do [this] for other faculty and students, to make them feel welcome and supported in the same way that the McMenamins said welcome to me,” Studenmund said.

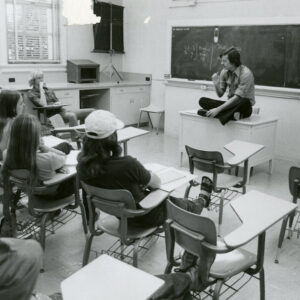

Studenmund had chosen the place around which the rest of his career would center, though he did not yet know it. In his first few years, Studenmund taught, assisted with the track team and took on rebuilding the economics department. He became the department’s chair for the first time in 1975, with all four other economics professors leaving the school in the middle years of that decade.

“My first administrative task was thrust upon me because I was the only economist left,” Studenmund said.

In 1986, Studenmund published the first edition of his econometrics textbook, emphasizing the practical applications that he felt were missing at Cornell and that he prioritized in his instruction. Four years later it became a bestseller.

The East Coast still called Studenmund back from time to time. He took a year on sabbatical and lived with Dave in Boston, where his future wife Jaynie was residing. As Dave moved through high school and college in the 1970s and 80s, Dave recalled his relationship with Studenmund maturing to one of peers. Spending the summer with one of his sisters and his brother at Studenmund’s cramped LA apartment in 1972, Dave said he remembers most how Studenmund waited at the gate as Dave’s departing flight sat delayed on the tarmac for two hours.

“That’s the sort of thing you come to expect from Woody once you get to know him,” Dave said.

‘Excellence and equal opportunity’

Studenmund is the first to admit that his hiring came at a time when connections often carried more weight than merit. While at Cornell, Occidental personally contacted Studenmund for a teaching position. He arrived at a college significantly whiter and more conservative than it is now.

“When I arrived, the entire economics department faculty were all white males who wore ties,” Studenmund said, ribbing at his more laid-back style of dress, which combined with his youth got him mistaken for a student in his early years.

Conversations around diversity at Occidental were just arising. “Oxy Faces Growing Chicano Environs” read a headline in the November 3, 1970 issue of The Occidental written by Rich Reyes, a Mexican-American student who called for the College to stop segregating itself from the growing Latino community in NELA. A few months later, on February 2, 1971, one op-ed led with: “Minority Scholarships: Where Has All the Money Gone?”

“In Marxist terms [Occidental] is an institution which serves to perpetuate the existing class structure,” wrote Dan Crawford, the author of the latter article. “If you do not believe it ask any black or Chicano in the surrounding communities. They will tell you that you have to be white and you have to have a lot of money to go to Occidental.”

In 1988, the College appointed its eleventh President John Brooks Slaughter — its first-ever Black president. From the beginning, Slaughter signaled diversification as his main priority, looking to increase minority enrollment and connect more with LA. His onboarding was met with resistance from certain trustees and enthusiasm from many students. According to archival articles, Slaughter’s first year as president was eventful. Debates raged over removing crosses from the Herrick Interfaith Center’s grounds, the establishment of a new multicultural dorm in Bell Young Hall and divestment from South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Slaughter said he left his position as chancellor at the University of Maryland College Park for the chance to work with undergraduates at Occidental.

“I was very pleased when I realized that students and faculty at Occidental wanted to improve the diversity on the campus and wanted to focus more on multiculturalism,” Slaughter said.

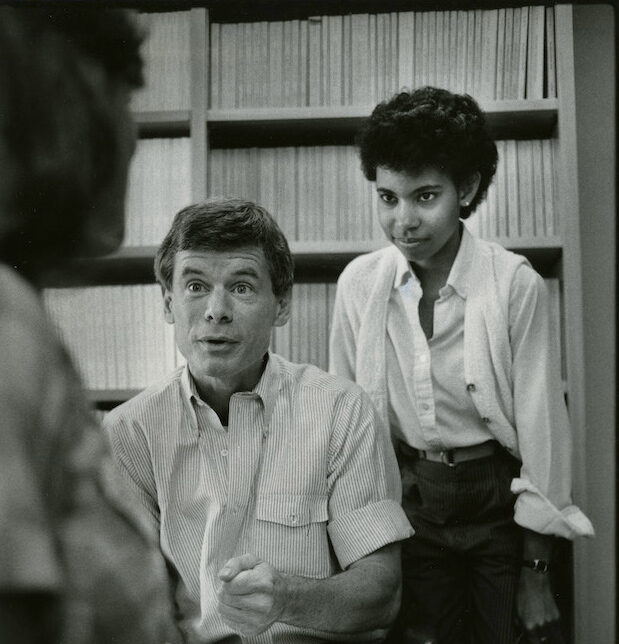

Slaughter quickly developed a positive working relationship with Studenmund — who was approaching 20 years at the College — particularly when it came to the financial aspects of developing Occidental’s new strategic plan.

“I appreciated his candor and honesty,” Slaughter said. “I didn’t want people to say yes, just because I was the president. I wanted them to give me their honest opinion and Woody always did that.”

At the time of Slaughter’s appointment, Studenmund had spent four years as director of the Core Program and had just assumed the role of associate dean of the faculty. He had focused most of his energy on the economics department, which by 1981 had become the College’s most popular, with female students outnumbering men in the mid-1980s, according to a 2018 feature in Occidental Magazine.

Studenmund would take on four different roles during Slaughter’s presidency, which he said he did because he believed in the evolving mission of the College and its diversification.

“[Slaughter] was an extremely caring, wise person,” Studenmund said. “And he cared very much about making Oxy a liberal arts college for all of California, and not just for a small subset of California.”

Studenmund emphasized that teaching remained the source of his joy. Administrating was something he did when called upon.

“To me the focus is Oxy,” Studenmund said. “And so trying to help Oxy achieve its goals is what led me to want to be in administration.”

During Slaughter’s presidency, Occidental’s non-white student enrollment grew from 25 percent to 43 percent, according to a 1999 profile in The Chronicle of Higher Education. His presidency was not free of controversy, as ambitious programming precipitated budget crises and high turnover. Some speculated his departure was forced — “Has Multiculturalism Been Slaughtered by Trustee Agenda?” asked the headline of The Occidental on September 4, 1998 — but Slaughter said he left due to a contractual obligation mandating his retirement at age 65 and to pursue other challenges.

“The College received more national recognition during the time I was president,” Slaughter said. “It certainly proves that you [can] have excellence and equal opportunity at the same time without losing quality.”

Having left after 11 years, Slaughter was nonplussed to learn that Studenmund has stayed for 50.

“It doesn’t surprise me,” Slaughter said. “Woody loves Occidental.”

Though he joined the administration to help the institution, Studenmund said he missed the classroom. In 2004, entering his thirty-fourth year at the school, he returned to teaching full-time.

‘That sticks with you forever’

Off-campus, a different shift cemented. Studenmund’s fortuitous move had stuck. He had traded snow for sun, the Phillies for the Dodgers, and the bachelor pad where his siblings crashed in 1972 for a home, a wife, and two children.

After spending a year at Pitzer College, Studenmund’s son Scott Studenmund left to join the Army Special Forces in 2009. He graduated from special training two years later as an Army Green Beret and by all accounts excelled.

In 2014, on a second deployment in Afghanistan’s rural Zabul Province, Scott’s unit came under fire. Scott, three other U.S. soldiers and an Afghan sergeant climbed a hill to a better position. They turned on their infrared strobes and vision goggles to see through the expansive night, and so that arriving air support could distinguish them amid the dark.

An Air Force controller gave an arriving B-1 bomber — not normally used for close air support — mistaken positions. Because the plane could not detect infrared strobes, it dropped two 500-pound bombs on Scott’s hill.

Scott and five others were killed shortly before Scott’s twenty-fifth birthday. The deaths remain the deadliest “friendly fire” incident of the Afghanistan War.

Studenmund does not like talking publicly about the incident and has made only a few exceptions. In 2017, when he and three members of Scott’s unit spoke to 60 Minutes’ Bill Whitaker, Studenmund declined to discuss his son specifically. He went on the show to decry the technological failures leading to his son’s death and to dispute the findings of the Army investigation, headed by General Jeffery Harrigian, which placed blame on the unit’s commander Derrick Anderson. Studenmund and the interviewed soldiers characterized that conclusion as unfair. They pointed to the B-1 bomber, worrying that its inadequacies would get more service members killed.

“When we send our soldiers into battle, it’s wrong to have them using a weapon system which isn’t capable of doing what it’s supposed to be doing,” Studenmund told Whitaker. “It’s not murder, but it’s close.”

Now Commander of U.S. Air Forces in Europe and Africa, Harrigian directs U.S. airpower across more than 19,000 square miles.

Jonathan Veitch, president of Occidental from 2009 to 2020, presented Scott with a posthumous degree at the Class of 2015 commencement ceremony. Studenmund accepted the degree on his son’s behalf.

“I firmly believe that if each American did one more thing to solve our country’s problems, we could have the country for whose aspirations Scott was willing to die,” Studenmund said at the ceremony.

Nearly seven years have passed since Scott’s death. Studenmund now serves as the inaugural faculty advisor for Occidental’s Veteran’s Programs, an initiative that took shape around the formation of The Barack Obama Scholars Program in 2017 to provide a community for students transitioning out of the military and into student life at Occidental. Studenmund said his involvement came when he was named to the Obama Scholars committee.

“I was asked to do it, and I threw myself into trying to do it,” Studenmund said.

Nathan Graeser, a social worker and Army chaplain named as Director of Veteran’s Programs in 2019, said the Veteran’s Programs initiative acts as an important way to maintain a community for students leaving the uniquely all-consuming nature of military service. He noted Studenmund as a steady presence for student veterans.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever seen a surfer just waiting for their wave,” Graeser said. “That’s what [Woody] reminds me of.”

The COVID-19 pandemic halted the initiative just as it began, but Graeser said he hopes to restart the program in the fall. He highlighted the necessity of providing a space for veterans to process often harrowing experiences together — Graeser himself fell into counseling work after a friend died serving in Afghanistan.

“It’s very hard to deal with grief outside of the context of the community we live in,” Graeser said.

After spending time with Scott’s colleagues following his son’s death, Studenmund said he has come to understand the specific goals of veterans as they search for a career after the military. Alexander Borges (senior), one of two veteran economics majors who Studenmund advises, said he believes Studenmund has the ability to understand where student veterans are coming from.

“When you have family in the military, you also become part of that family, that group, and that culture, and that’s something that sticks with you forever,” Borges said.

He also said that Studenmund has been an important mentor and advocate.

“He’s an awesome, economics rockstar,” Borges said. “He’s definitely been super supportive since I came to Oxy and he’s always there when I need him.”

‘I plan on coming back’

From the economics department to the administration to veteran’s programs, Studenmund’s influence has reverberated across the decades. Art Peck ‘77 — Fortune 100 CEO, investor and entrepreneur — said he remembers Studenmund as an engaged and demanding professor and a well-known presence on campus.

“He wanted to invite people in to experience his passion for the subject matter that he loved,” Peck said.

Peck took five or six classes with Studenmund, and he is convinced Studenmund’s letter of recommendation got him into Harvard Business School. Peck and Studenmund have kept in touch, and when Peck’s son and daughter attended Occidental they each had Studenmund as an advisor for a time. Peck described his relationship with Studenmund as one of the most enduring friendships of his lifetime.

Some 40 years later, Davis first met Studenmund when applying for a grant he oversaw in her sophomore year, and went on to take Studenmund’s managerial economics class and become his advisee. She was rejected for that grant the first time — not because her application was poor, but because Studenmund wanted to challenge her, she said. His classes have the same atmosphere.

“In his class, you always have to be prepared for something new or something different,” Davis said.

In a field that has been historically dominated by men, Davis said that Studenmund’s emphasis on public speaking and problem-solving has helped her develop confidence.

“When there aren’t as many women in the room, sometimes it can be harder to speak up,” Davis said. “That wasn’t an option in his class. I had to speak up. Practicing that skill in his class has really served me well.”

Due to the difficulties of remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, Studenmund has taken a hiatus. But that does not mean he has completed his nine innings at Occidental.

“As soon as I can teach in person, I plan on coming back,” Studenmund said. “Certainly through May of ‘22, maybe longer.”

Studenmund said he is proud of how Occidental has changed, and highlighted that the economics department now has one of the highest ratios of women faculty and faculty of color at a co-ed institution.

“Oxy is just a tremendously better place than it was when I first came,” Studenmund said.

Reflecting back, he was unequivocal about his decision to stay at Occidental for more than half a century and two-thirds of his life.

“I would certainly make the same choice all over again,” Studenmund said.

After the publication of this article, Studenmund informed the author that he has decided to retire at the end of the 2021–2022 academic year. The decision will round out his Occidental career at 52 years.

Correction (March 26, 10:11 am): An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that Scott was Studenmund’s eldest son. That sentence has since been updated.

![]()