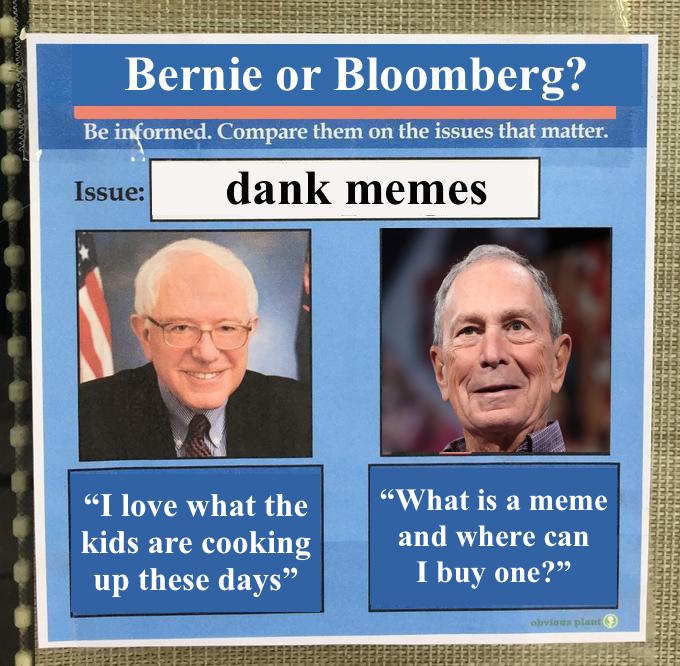

Tell me if you’ve heard this one before: an old guy tries to hang with kids by adopting one of their mannerisms to poor effect. There’s even a meme for it — actor Steve Buscemi, dressed like a teenager, eagerly asking a group of teens, “How do you do, fellow kids?”

The Buscemi meme was my first thought when news broke that former New York City mayor and presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg had paid internet influencers to make memes for him. In an attempt to garner interest online, Bloomberg began working with Meme 2020, a group consisting of Instagram memers with millions of followers such as Tank Sinatra and Middle Class Fancy. The memes, which depict Bloomberg struggling to comprehend meme culture as he conscripts some of the internet’s most successful memers, are meant to be ironic, but they come off as fake and conceited while revealing the weaknesses in his campaign.

I know a bad meme when I see one. In 2017, I started Oxy Memes for Fountain-less Tweens, a Facebook group dedicated to Oxy-related memes that has 1,134 members as of Feb. 24, and became one of its top contributors. Because of this, Herd Media Group offered me a job to make college-related memes with a starting salary of several thousand dollars. (I turned it down because I could not see a long-term future in making memes.)

With this accumulated meme experience, I can tell you that Bloomberg’s meme campaign is contrived and unfunny. In a meme posted by Middle Class Fancy, for example, Bloomberg asks if “Mr. Fancy” will post a meme to “make him look cool for the upcoming democratic primary.” The language used is awkward in a way that feels forced, as if Bloomberg needs to focus every ounce of his being into being funny.

Bloomberg’s approach to memes reflects his approach to his campaign — he’s throwing money to the wind and hoping something works. In this case, he’s spending $1–1.5 million for influencers to post lazy screengrabs. But paying for memes defeats the point of what memes are all about: spontaneous content whose production and dissemination are available to all.

Compare Bloomberg’s memes to those about his competitor, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont. Sanders hasn’t actually commissioned any memes, but his campaign has sprouted many. Most recently, the “I Am Once Again Asking for Your Financial Support” meme spun off from a December 2019 campaign video of Sanders asking voters for donations. As it does, the internet turned Sanders’ request for money into a request for anything. Nothing suggests Sanders — or anyone else — paid for this meme or other Sanders memes such as 2016’s “Bernie or Hillary.” In contrast, by paying for memes, Bloomberg reinforces his persona as a disconnected billionaire. While he tries to play the memes off as self-aware, it’s difficult to hide the fact he’s shelling out millions of dollars to make himself look like a fool — not a good look when he came out of his first debate looking like an actual fool.

One could argue that despite their poor quality, Bloomberg’s memes will still garner him valuable attention over other candidates. But the attention ultimately serves to highlight the flaws within his campaign. Bloomberg paying millions of dollars for memes — as opposed to funding, for example, canvassing efforts or voter registration — demonstrates his reliance upon wealth, not his actual leadership, for running his campaign. It’s as if one of Bloomberg’s grandkids showed him a single meme and, belayed by his limitless self-confidence (and wealth), he decided to jump on the meme train without any thought.

Memes for candidates such as Sanders work because of the candidate’s personality and policies, not their wealth. Sanders is popular both because he pushes for programs such as Medicare for All and because he works with pop culture figures like Killer Mike and The Strokes to garner interest in his campaign. Hell, Sanders and Killer Mike’s collaboration is a meme itself, and the only payment Sanders made for it was probably footing the lunch bill. The Bernie or Hillary meme became popular in 2016 because the people making them wanted to illustrate in meme form that Sanders was the better Democratic candidate. Meanwhile, Bloomberg lacks this grassroots memery. He’s paying big-name Instagram influencers and even casual users $2,500 a month to promote him — even though said users may not even actually support him.

Bloomberg’s conscription of the internet’s influencers offers a cautionary tale about how to exist in today’s meme culture. There is the organic approach, in which memes such as “I Am Once Again Asking…” pop up freely, and there is the brute force method Bloomberg uses in his quest to become the presidential meme king. But no one makes a Sanders meme because they’re paid to — they do it because they want to. It’s this fundamental aspect of memery that Bloomberg completely misses. In the process, he loses both his credibility and finances.

A close look at the memes Bloomberg pays for speaks to his ethos, revealing his commitment to using his wealth to gain any advantage over his rivals. Candidates shouldn’t commit themselves to meme marketing, and instead should focus on being a candidate with good policy and social standing. No one has ever been elected on memes alone.

Thanks for coming to my TED Talk.

Pablo Nukaya-Petralia is a senior art history major. He can be reached at pnukayapetra@oxy.edu.

![]()