I was taught that I was not the expert of my body from a young age. As an 8-year-old, my parents decided I was done eating when I finished all of the food on my plate. At age 12, I started cutting calories after learning that we should only consume 2,000 per day. When I created my Instagram account at age 14, I was already susceptible to the hundreds of wellness influencers promoting “clean eating.”

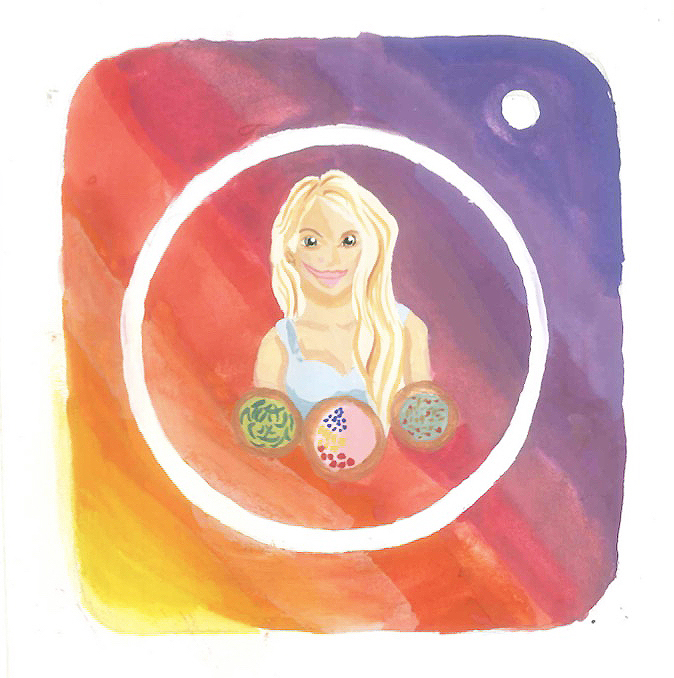

At first glance, wellness culture appears to be a harmless mechanism for keeping yourself physically and mentally healthy. Think of a sinewy blonde woman touting her açaí bowl and gushing over her health food e-book. But beneath this masquerade of health, there is a toxic notion that we are not enough. It implies that we are not supposed to be content with our bodies, working toward an elusive and warped sense of improvement. Wellness culture is diet culture reborn through social media. It profits off of our body insecurities, by telling us that we do not know what is best for our bodies.

Diet culture, born out of the societal pressure to lose weight and be thin, is a system of beliefs that glorifies a certain type of eating to achieve a particular body type. With its positive undertones and promises of weight loss, diet culture says that looking and eating a specific way will make us healthier and morally superior over those who don’t eat the way we do. By convincing women to hate their bodies, the diet industry is now worth $72 billion.

According to studies done by Linkfluence, wellness culture is on a similar trajectory. In the past two years, the global wellness market has expanded by 12.8 percent, making it a $4.2 trillion industry. Through “advertorials” — part advertisement and part editorial — wellness influencers peddle products like pro-collagen Chlorella supplement powder and everyday morning glow routines to their followers for pay from the company. They may gush over these products, but that’s probably because they’re getting paid.

Ultimately, wellness culture succeeds underneath a guise of authenticity and how genuine their lifestyle appears to the followers. But the artificial nature of social media makes this impossible, so the fact that the majority of wellness culture lives on social media should say something to us about the authenticity of this movement.

In 2015, Essena O’Neill, a former wellness guru, told her followers the content that she had fed them was entirely fabricated. She recaptioned each of her Instagram posts to reflect the truth behind them, revealing just how unhealthy she was. Since then, she has remained off social media.

Beneath these Instagram posts, we learn that our bodies should be in a perpetual state of improvement. The language we use in the wellness community suggests that eating “clean” or “raw” is the only way to achieve a healthy lifestyle. Clean eating has transformed from emphasizing awareness of food ingredients to enforcing a hierarchy of “good” and “bad” eating that idolizes adherence to a specific set of foods. It also implies that those who eat clean and keep their bodies free of processed food toxins are superior.

If we are constantly labeling food as either clean or dirty, we have a high likelihood of falling into unhealthy patterns. According to a study on 14- to 15-year-olds by the National Eating Disorder Association, those who diet are five times more likely to develop an eating disorder. Lee Tilghman, a formal wellness influencer, used to post clean comfort food and self-reflective captions. She recently revealed that wellness culture pushed her to develop orthorexia, an eating disorder that revolves around the obsession with eating pure and healthy foods. Now, she advocates for the end of wellness culture. We are so coaxed into obsessing over labels — clean, vegan, paleo and gluten-free — that we’re coming out on the other side with orthorexia, anorexia, bulimia and a screwed-up body image.

Wellness influencers don’t have the credentials to offer nutritional advice. In extreme cases, they are just flat out lying for profit. Take blogger-turned-convict Belle Gibson, for example. In 2014, Gibson amassed 230,000 followers, an app and a book deal and when she claimed clean eating was curing her of cancer. As it turned out, however, clean eating was not curing her — because she didn’t even have cancer.

So let’s stop taking advice from social media. Being healthy is not just about the way we eat or the way we cook— it’s about how we nourish ourselves physically and mentally. This looks like intuitive eating, a medically-approved philosophy that encourages listening to hunger cues to determine when to eat. For me, wellness looks like putting butter on my toast, going on a walk instead of a run and knowing that I am the expert of my own body.

Emma Robitaille is a senior Media Arts & Culture and Spanish double major. She can be reached at erobitaille@oxy.edu.

![]()