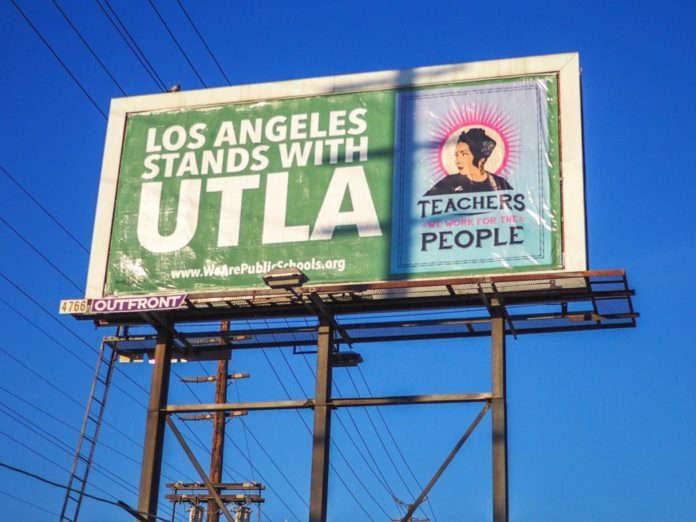

LA teachers went on strike Jan. 14, demanding higher pay, smaller class sizes and increased support staff. After extensive negotiations, the strike ended Jan. 22, when the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) board of education and the United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) union came to an agreement. During those six days, the Eagle Rock community extensively organized to support LAUSD staff.

“It feels like this strike is about saving public education … it comes down to ‘How do we keep our public education equal and equitable for all students?'” said Virginia Escamilla, a parent of two LAUSD students.

According to Escamilla, one of the major issues facing education today involves charter schools, specifically their funding and oversight. Part of the agreement to end the strike mandated that the board would send a resolution to Sacramento to urge state legislators to put a moratorium on new charter schools, allowing for researchers to study their effect before any more open.

“What the charter school system has created is a system pulling away from [equal and equitable public education] and leaving many schools behind and many students behind,” Escamilla said. “It’s not accountable.”

Julie Kang is a parent at Dahlia Heights Elementary School in Eagle Rock. As a member of the Parent Teacher Organization (PTA), Kang has focused on legislative advocacy.

“There’s a lot of money being made by privatizers. When a charter school opens up, they take private money but have none of the public oversight,” Kang said. “Once you know what is happening, it’s impossible to not get involved.”

According to Escamilla, who is a regular community organizer, the size and strength of the community response to the teachers’ strike surprised even her.

“The core of our communities is our schools. We entrust our kids to [teachers] every day, and we’re trusting that they are getting the education that they need to get in these institutions,” Escamilla said. “I think the natural inclination of the parent is to say that ‘I’m standing with my teacher.'”

According to Kang, it wasn’t just parents who overwhelmingly supported teachers. On the strike line, Eagle Rock community members who were not associated with the school brought boxes of food and offered supplies to the teachers, and many vehicles honked in support.

The Eagle Rock restaurant Joy offered all striking LAUSD staff a 50 percent discount and gave soup to strikers at nearby Buchanan Street Elementary School.

“We have a lot of regulars who are teachers at LAUSD,” said Manager Liz Liu. “We felt we were so close in the community with those people that we felt we wanted to show support for them in that way.”

According to Escamilla, who was a freshman in Eagle Rock high school during the last teachers’ strike in 1989, current technology made this strike very different from the 1989 strike in terms of community involvement.

“What leads to people being informed is this darn little thing: [gestures to phone]. Social media did not exist in ’89,” said Escamilla. “Social media was my go-to for articles and information, and it was my go-to to organize this community.”

According to parent Lindsey Clough, one of the ways that she chose to show solidarity with teachers during the strike was by keeping her kindergartener home from school and instead having him participate in a strike-school. A strike-school is a childcare option that is hosted by parents in the community to teach and watch each others’ children. Strike schools made keeping children home more accessible to parents who might not have the resources to do so otherwise.

Many Eagle Rock strike-schools were organized using a spreadsheet that Clough and other parents created. The sheet allowed parents to sign up to host or have their child attend a strike-school and included information on whether or not a school would include lunch, since for some kids school lunch is their only dependable meal.

“I got really frustrated when the media kept saying ‘600,000 parents are thrust into chaos‘ and I kept thinking, ‘No, we’re not, we’ve known about the strike for a month, we’re known the possibility of the strike for many months, and we’re actually very well organized,'” Clough said.

According to Escamilla, at Dahlia Heights Elementary School anywhere between 45–55 students showed up on a daily basis during the strike’s six school days. Those numbers varied across LAUSD, and in some schools, many more students showed up out of necessity.

According to Escamilla, the strike itself was a valuable educational opportunity, and she made sure to talk to her child about it.

“We talk about it a lot, so that they understand what it is that their teachers are fighting for. [For them,] it wasn’t, ‘We don’t have any school, it’s vacation,’ at all. They were out there with us on the lines,” Escamilla said.

Clough said that even the youngest LAUSD students seemed to have some understanding of what the strike meant.

“My kid is only five and a half and he understood. We went out to the picket line every day. And I think that taking them there and showing them, I think they need to see it with their own eyes,” Clough said.

“I just really want people to understand how big this strike was,” Escamilla said. “It’s not about specifics. It’s about the big picture of an institution that was put in place well over 200 years ago to make [education] accessible and equitable for all children, and when you undermine that, it speaks loads about our democracy. It speaks loads about what our communities are. So that’s what’s at stake right now.”

![]()