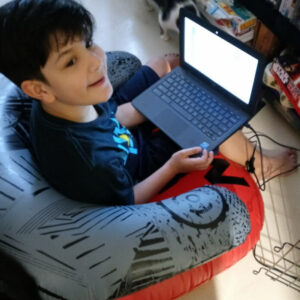

Monica Campos is studying to be a teacher. Sequestered at home in Eagle Rock, she’s taking anthropology, art and Spanish courses in hopes of earning a Child Development degree from Los Angeles Trade Technical College. But like so many students during the pandemic, she is burdened by a host of other responsibilities that make full focus on her academic success impossible. Campos is a mother of two boys, ages 7 and 8, both of whom have special needs and are struggling with virtual learning.

“It’s chaos. Every morning is a battle,” Campos said. “My kids are miserable.”

Campos and her sons begin each day around 7:30 a.m., walking to a local school to pick up food before setting up their small station at home for the school day ahead.

“It’s hard for them to situate well, ‘How come I can’t go to school in my pajamas if I’m home? You just told me that I’m done with school, but why do I have to do homework again?’” Campos said. “And they’re just not having it. They’re confused.”

One of Campos’ sons has ADHD and other challenges, and the other has autism. Campos said her sons’ teachers have expressed frustration when they chew gum or an eraser, or get out of their seats to walk around, and that their Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) are often not followed.

“They go to school from 9 to 12:30 and I’m in my Zoom classes at about the same time. So I’m running back and forth between children and explaining to my teacher, ‘Look, I’m sorry, I gotta go deal with this. I can’t stay in class,’” Campos said. “Besides the tears, it’s like, ‘You know what? Take a break from the homework because I can’t do it.’”

Campos’ struggles with online schooling represents those of many American families during the pandemic, those who can’t easily afford a separate bedroom for each child, high-speed Internet access or a private tutor or aide.

In the sprawling Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second-largest school district in the nation after New York City, these inequities are laid bare. Of the district’s 600,000 students, about 80 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, over 27 percent are English language learners and 12 percent have some kind of disability, according to Tasha Busch-Arratia, a pupil services and attendance counselor (PSA) at both Eagle Rock High School (ERHS) and Franklin High School (FHS). Most LAUSD families don’t have the spacious work areas or gleaming personal computers depicted in the district’s back-to-school guide.

Ronald Solórzano, an education professor at Occidental, expressed concern that online schooling would exacerbate the country’s educational inequity, which he witnessed firsthand when he taught for 13 years at several elementary schools in East Los Angeles, a primarily Latino area.

“Some people suggest just canceling the school year because it’s not working. In poor neighborhoods where parents are essential workers, the kids have little to no supervision during class. If they’re 5, 6, 7, 8 years old, it’s problematic,” Solórzano said. “Children are feeding off their families’ anxieties. There’s more anxiety, different sleep patterns, nightmares. There’s a lot of consternation in poor homes right now.”

Peter Finestone, an education representative for the Eagle Rock Neighborhood Council (ERNC) and a parent of three, said he too can see the mental health effects the pandemic is having on his children’s education, even though they are in a more fortunate situation.

“I have one son who is 10 years old, and he’s depressed,” Finestone said. “It’s really heartbreaking to see one’s own son, at the age of 10, say, ‘I’m depressed.’ You don’t expect to hear that from someone so young. We’re trying to find a way to let him know that what we’re going through now is not forever.”

Every parent interviewed for this article listed social isolation as one of their biggest concerns for their children this year. Campos said interacting with friends solely over a computer screen has dampened her children’s outlook, particularly for her son with autism.

“They think they’re socializing but that’s not socializing. They need to play, get into little arguments, throw toys at each other, that’s playing. They need to go get dirty,” Campos said.

What Finestone and his family are aiming to do is calibrate their expectations for what this strange, lonely year will yield.

“We always expect that, like, he should be reading a book or count to 1,000 by the age of 7. I’m like, ‘Just slow it down. Learn how to count to 100. Learn to pronounce the word,’” Finestone said. “Parents always want their kids to excel, like, be the best they’re gonna be. I think parents are having to really learn what they can expect from their kids.”

Across varied financial situations, many people indicated a pandemic-induced desire to slow down the default setting on America’s educational treadmill, or to step off it altogether. Finestone spoke of turning off his sons’ Zoom school to take them and their dog to the park. Chris Oswald, a science teacher at ERHS, said he’s prioritizing quality and accessibility of work he assigns, rather than quantity.

From frequent standardized testing to an introduction of worksheets as early as kindergarten, American schooling moves at a frenetic pace that some experts believe is meant to compensate for the unevenness of its students’ ability to thrive in it.

“They’re easing up on high-stakes assessments that they would otherwise be giving. Opportunity to learn is a testing validity issue since children who need education the most are getting it the least,” Solórzano said. “There has to be an asterisk next to this school year and next school year.”

Maggie Darett-Quiroz and her family have been through their fair share of challenges this year. Darett-Quiroz’s husband underwent a major, high-risk surgery, and their family now must fret over both helping him recover and avoiding the coronavirus. Her 7-year-old daughter, Priscilla, is an advanced learner who is being tested for giftedness, which, her mother says, can be its own kind of special need.

“It’s kind of difficult when a child is advanced, because I do see that sometimes the teacher is maybe struggling with all the kids. But my little girl is on the side, saying ‘I’m just bored,'” Darett-Quiroz said. “I had to find ways to make sure that she’s up to par, that she’s being challenged.”

Darett-Quiroz spoke to the principal of the school, asking if her daughter could be challenged more in class. She describes herself as an involved mom and a fierce advocate for her daughter’s education, determined to help her daughter succeed despite this year’s challenges.

“I think the world is in survival mode, or at least we’re in survival mode,” Darett-Quiroz said. “But if you can learn one thing this year, it’s not a lost year.”

With life moving online, LAUSD teachers have had to embody this adaptability, learning new technologies and developing strategies to maintain students’ love for learning and connections to each other, according to Oswald.

“[My son’s teacher] understands how hard it is. She’ll get out her mandolin before they come back from the Zoom [after] a break. Forget about the lesson plan, for 10 minutes they play songs,” Finestone said. “But most importantly, she knows when there’s a kid who’s having a hard time, she could detect if there’s some kid in the class who emotionally is not there, and she’ll be like, ‘Oh, John, what’s going on, son?'”

For Oswald, as a science teacher and counselor, forging these connections is hard online, especially with all the challenges his students are facing. Some go to a Starbucks for their Internet connection; many find the school week so taxing that they don’t attend office hours or tutoring. His only lifeline to his students’ lives is on Zoom.

“We don’t necessarily force them to turn their video on, so if they’ve got their screen off, we don’t know if they’re really engaged in the class,” Oswald said. “But again, if you’re going to turn your screen on you’re inviting somebody into your world. That can be problematic.”

Despite these challenges, Oswald is adamant that this cannot be characterized as a “lost year.” One bright spot to online learning has been the plethora of digital resources he would not have used in a traditional classroom, which have helped Oswald creatively rethink the presentation of his science curriculum, he said. He is finding that his students are still able to produce strong work.

“Instructionally, I think that there are some very high level things [being taught and learned],” Oswald said. “There are still things to be gained from it and there’s still some real academic integrity that’s taking place.”

Providing basic educational resources is a goal that is often stalled by national and local politics, according to Solórzano.

“We have the wherewithal, in this country, to provide everything students need,” Solórzano said. “But do we have the sense that we can do this in poor communities? No.”

Though they may not have the institutional support they need, everybody interviewed is doing their part to fulfill a goal within their own sphere of influence. District officials are looking at ways for students to make up lost credits, according to Busch-Arratia. Busch-Arratia herself spends most of her day attempting to re-engage students with learning, providing counseling and services and responding to crises.

Campos said she wants to retain her children’s love for learning, and her own, as she works towards becoming a teacher. Until then, she logs on to her daily Zoom class and her children to theirs, mother and sons equal in their resilience as they mute themselves and their day begins.

![]()