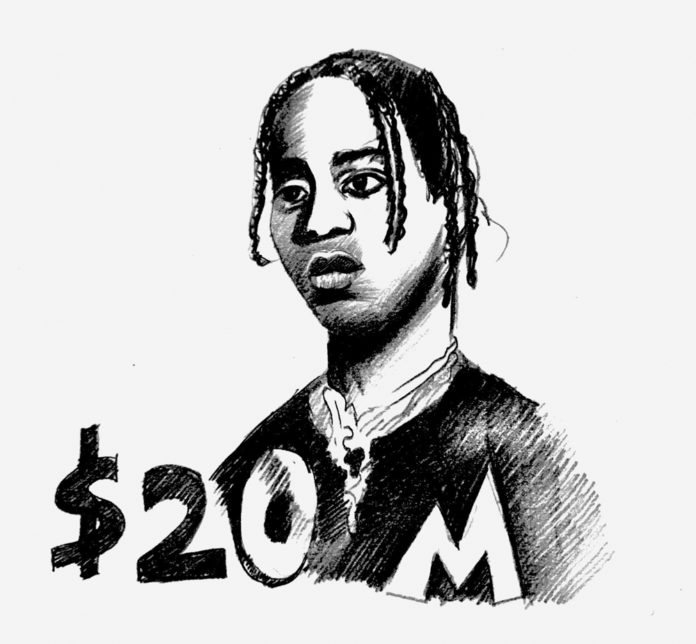

Three Six Mafia founder DJ Paul is taking a stand against Travis Scott, rap’s stickiest-fingered superstar. The Blast reported April 23 that the Memphis born rapper-producer recently filed a copyright lawsuit claiming Scott lifted the chorus from “Tear Da Club Up” and repeated it on “No Bystanders.” Without clearance, this impersonation is merely piracy. Paul attests that Scott’s version has a “cadence and sound” which is “virtually identical and strikingly similar” to his original record from 1995. He seeks $20 million in damages for this unacknowledged contribution to Scott’s Grammy-nominated album “Astroworld.” After spending half a decade repackaging the ideas of other artists, it is only fitting that the Houston socialite’s plagiarism is finally on the books. Scott’s recent accomplishment is a result of his shift in creative responsibility. By dropping back into the wider role of a curator, he organized space for the 21 features littered throughout his record. Professional presentation and unlimited resources are not substitutes for skill, yet the 26 year old ascended on account of the former. It is long in the rearview mirror, but his unexpected appearance on Kanye West’s 2012 record “Cruel Summer” once invited suspicion that a budding career was manufactured by executive forces. Whispers that Scott may be an “industry plant” persisted online until he was anointed a sophisticated synthesis by an enabling press machine.

To his credit, “Astroworld” is a small step away from the failing formula of his two previous albums. Even so, this does not erase a past of adaptation without homage. When he screams Future’s trademark adlib “Straight up!” it is a minor yet blatantly unoriginal verbal tic. He has mostly worked this effect out of his music, but it was frequently deployed throughout his formative mixtapes. In 2014, a Dutch graphic designer alleged that the rapper stole his fan-made album artwork for the mixtape “Days Before Rodeo.” Two years later Scott put his name over original music by singers K. Forest and Starrah. The latter recorded vocals on an early conception of “Pick Up The Phone” but was later replaced by Scott without permission or notice. Just last year producer Tommy Brown suggested Scott made his first inroads with Kanye after showcasing instrumentals he did not make himself. These incidents appear at every stage of his career.

On the surface, Scott projects himself as a stylist of American streetwear and European high fashion. When Kanye swerved into his quest to redefine luxury, it created a commercial relationship between these two tiers of industry. Historical fashion houses found a way into contemporary popular culture through celebrity rappers because their own tradition waned in relevancy. It was a way to align with the times and tie themselves to influential stars of the perceived counterculture. New York rapper A$AP Rocky elevates his career by blurring these lines with pretentious pose after pretentious pose. He hasn’t made a compelling record since 2011, but his prestige persists because lazy rapping is excused if it builds a bridge to conceptual art.

This transformation is evidenced by Louis Vuitton’s recent appointment of art director and streetwear post-modernist Virgil Abloh. The march to that hire birthed the likes of Rocky and Scott as cultural interpreters. In Kanye’s trickle down economy of artistic ideas, he needs a protege, and when Kid Cudi’s career imploded, Scott slipped in to become the favorite son.

Scott works as an operative vessel because of his close collaboration with Rap-A-Lot producer Mike Dean. His hits rely on the atmosphere directed by Dean and fashioned as a substitute for a private personality. Without this effect, Scott’s catalog is filled with diluted trap experiments. His lyrics are contextless and ephemeral because they rarely propose a distinct psychological, spiritual or emotional crisis. They begin in the middle of a situation and their contents fall away only to be replaced by a new flex. It is all about what he has and rarely about what he wants, never mind who he is. The missing piece on every Travis Scott record is the inner life of the artist himself.

DJ Paul’s case seems irrefutable. He released a statement to clarify, “There is no beef, just business.” The original “Tear da Club up” is aggressive and intense beyond Scott’s deliberate and dull profanity. Its collective chant is the sound of a mosh pit caving in on itself. A clearer mental image appears in association with the verb tear. There’s a sharpened violence situated within the instruction to take something whole and destroy it into fragments. If Scott used the hook out of admiration, then why not credit older artists instead of denying and concealing their signature so that new listeners cannot appreciate what he believes is an improvement? Three songs later, on “5% Tint,” he flips Goodie Mob’s track “Cell Therapy” to juvenile effect. The bleak spirit of that record is transformed into chic sludge. We’ll soon find out if money is the only thing that stops Travis Scott from biting everything in his path.

![]()