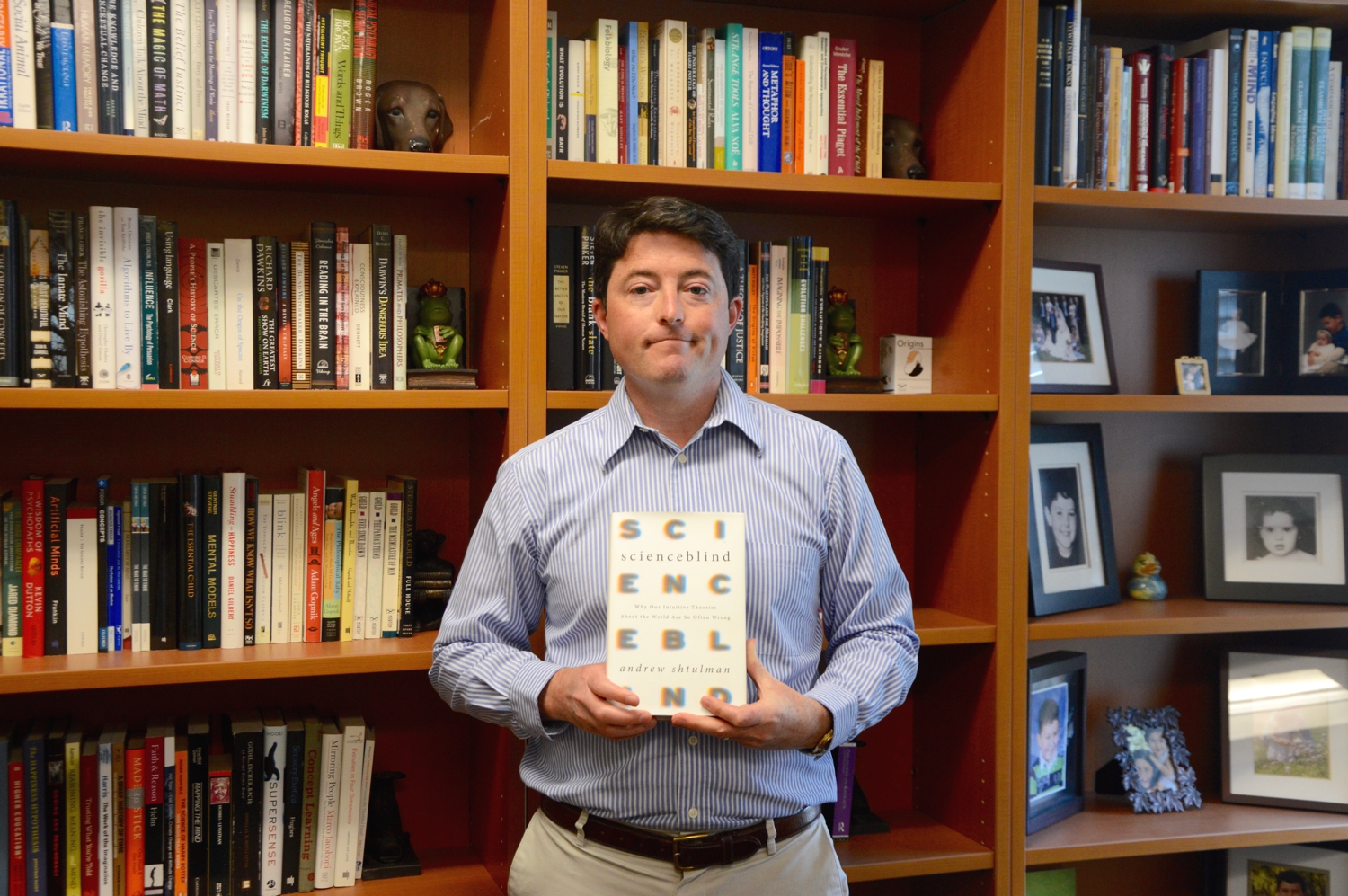

Millions of people believe that dinosaurs coexisted with humans, that the continents are stagnant and that the sun rotates around the earth, according to Chair of the Cognitive Science Department Professor Andrew Shtulman. Shtulman’s latest book, “Scienceblind,” unpacks why we often reject science in defense of our childhood beliefs. Students, faculty and science enthusiasts gathered at a lunch-time lecture in Choi Auditorium with Shtulman Monday, April 17, at 1 p.m. to discuss the findings in “Scienceblind.”

Shtulman began with a powerpoint replete with statistics, quotes and images highlighting the stark polarization between science and intuition. Shtulman described how science is counterintuitive and contradicts ideas individuals have held since childhood. Through his research and his most recent book, Shtulman hoped to inform the general public of these misconceptions.

“Intuitive theories are systematic explanations for how the world works that we develop in childhood and maintain across the lifespan,” Shtulman said. “Researchers in my area of psychology, cognitive development, have studied intuitive theories for several decades, but few people outside this area know what they are or how they influence our attitudes, beliefs and behaviors.”

Working from both the comfort of his home and coffee shops, Shtulman completed “Scienceblind” in two and a half years. In addition to his writing career, Shtulman has earned degrees in psychology from Princeton and Harvard and has published several dozen scholarly articles on conceptual change and development that have featured in CBS News, Scientific American and The New Yorker.

“I have always been fascinated by differences in how we perceive and understand the world — differences across age, across cultures and across individuals,” Shtulman said. “I also see psychology and cognitive science as routes for improving our understanding of the world and our understanding of each other.”

He stated that intuitive theories are limiting since they are typically inaccurate. For instance, physicists — individuals who have dedicated their lives to the pursuit of scientific knowledge — still cognitively rely on intuition. Shtulman discussed a study in which a group physicists were asked to imagine two balls of different masses and determine which would land first after they were dropped simultaneously. Though it is scientifically proven that the two balls will land at the same time, the physicists’ brain scans illustrated that they initially may have thought the heavier ball would land first — a misconception contradicting what they learned throughout their career. Jake Palumbo (sophomore), who attended the talk out of interest, found this contradiction to be of particular interest.

“The continual tension between misconceptions about our intuitions and foundational knowledge was a striking dichotomy in Dr. Shtulman’s presentation,” Palumbo said. “It seems that Dr. Shtulman has hit the nerve of how we as humans can seek a fullness in perspective on life.”

Shtulman explained that most people openly acknowledge their intuitive beliefs that contradict science, sometimes clinging to non-scientific theories of motion, energy and evolution. Others unknowingly hold beliefs that contradict science regarding matter, life and growth. For Elizabeth Hribal (junior), these real life concepts of cognitive science drew her to the event.

“As a cognitive science major and someone who recognizes the validity of science, it was very interesting to hear how the beliefs we develop as children stick with us and inform or misinform us even throughout college,” Hribal said.

Shtulman stumbled upon articles across different areas of research that made his approach to his book more interdisciplinary. He stated that these overlaps demonstrate the importance of collaborative research.

“While writing ‘Scienceblind,’ I discovered connections among studies I had never seen before — methodological connections, empirical connections and theoretical connections,” Shtulman said. “Researchers are responsible for knowing previous findings in their particular area of study, but we often overlook relevant findings in neighboring areas.”

Although Shtulman is a professor of cognitive science and psychology, he said “Scienceblind” is applicable to those who identify as “non-science people.”

Although he began “Scienceblind” more than two years ago, Shtulman noted that his findings are more relevant than ever under Trump’s administration, with Scott Pruitt, who is an avid climate change denier, as the head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Shtulman discussed how intuitive theories are largely misleading when evaluating decisions of public health and the environment, particularly decisions that politicians make. When politicians routinely deny scientific facts such as climate change, evolution and the safety of vaccines, they deny the pertinence of scientific research.

“There are sociological and ideological reasons why politicians deny science, but there are also conceptual reasons,” Shtulman said. “Science is counterintuitive. We don’t trust ideas that conflict with intuition, but sometimes it’s our intuition that shouldn’t be trusted. The purpose of ‘Scienceblind’ is to highlight areas of knowledge where our intuition cannot be trusted.”

“Scienceblind” is currently available for purchase on Amazon.

Have a tip? Email us at weekly@oxy.edu or tweet us @OxyWeekly.

![]()