As a 40-year–old Italian man pantomimed oral sex on a Greek stripper and the smell of alcohol, sweat and unchecked testosterone perverted the air, one thought popped into my head.

Men suck.

That is, masculinity sucks, and it is men — and men alone — that have created and perpetuated our current, perverse definition of masculinity. It’s a masculinity that protects men from responsibility, tells men to enjoy abusing women and women to enjoy being abused, and equates the desecration of human life with “high school behavior” and “locker room talk.” It’s a masculinity that teaches men — from Mykonos, to Hollywood, to Washington — how to harm others and get away with it.

But first, some context.

This past summer, a family vacation in Greece overlapped with the trip of two friends from high school, who I’ll call Anne and Kay. I accompanied them to the island of Mykonos, which as I discovered, is notorious for its batten-down-the-hatches, sh*t’s-gonna-hit-the-fan beach raves.

That night we went to one, and the harassment began instantaneously. Men of all nationalities and ages groped, stared at, catcalled and invaded the personal spaces of Anne and Kay. They never listened when Anne and Kay protested, but would occasionally listen to me if I physically removed their hands or pretended that I was dating Anne or Kay. We saw many of these men at our hostel the next morning; they would look me in the eyes and grin.

I learned several things that night, the first being that women are taught to understand harassment as an unfortunate byproduct of enjoyment. Despite the fact that the night entailed constant assault, both Anne and Kay told me the next morning that they had a great time.

The second was that too many men treat interactions with women like a game, where “winning” equals obtaining the woman. Men only stopped bothering Anne and Kay when I told them to. In their eyes, I had already obtained possession of these two women, and only the possessor’s objections were valid. I had multiple men “congratulate” me for having “scored.”

My third and most terrifying revelation was that this environment is a powerful intoxicant. It took more willpower than expected to prevent the compliments of other men from inflating my ego and sense of masculinity and power.

However, my newfound consciousness of these things does not make me any less of an apologist. I still fail regularly to call out this game of “out-masculinizing.”

A month after I returned from Greece, a male friend and I had a Lyft driver who made numerous uncomfortable comments about women — how he controls when and where he grabs his girlfriend and how he enjoys “going hunting” at clubs, among other things. He seemed to believe these comments were relatable.

I had two options: stand up to this man’s misogyny, or say nothing and stay on good terms with a sleazy male stranger. My moral compass pointed me towards the former. My internalized “bro code,” which valued the approval of the worst of men over the favor of the best of women, pointed me towards the latter — and it won out.

It is often easier to condemn the big things (intimidation, groping, rape) than the little ones. But the jokes, the snide comments, the bragging — these small things validate the bigger actions. People like my Lyft driver have probably run into hundreds of men like me — men who didn’t approve of his sexual misconduct but who didn’t condemn it. That absence of condemnation is equivalent to validation. It’s a subtle, if unintentional, wink: an acknowledgment of the game that’s being played and the exhilarating mischievousness of it all.

Whenever I discuss sexual assault and harassment with survivors, they usually express one common sentiment: I wish I had done more. Interesting. We don’t ask victims of burglary or arson to “do more.” We consider that law enforcement’s job. Only when it comes to sexual assault do we place the full responsibility of obtaining justice and running the conversation on the victim.

So yes, survivors should be the ones to lead the #MeToo movement. But they should not do it alone. Men are the common denominator here; we disproportionately assault and we disproportionally validate assault. When we place the burden of discussion on the victims, we allow the dominant perpetrators to dodge even contemplating their role in rape culture.

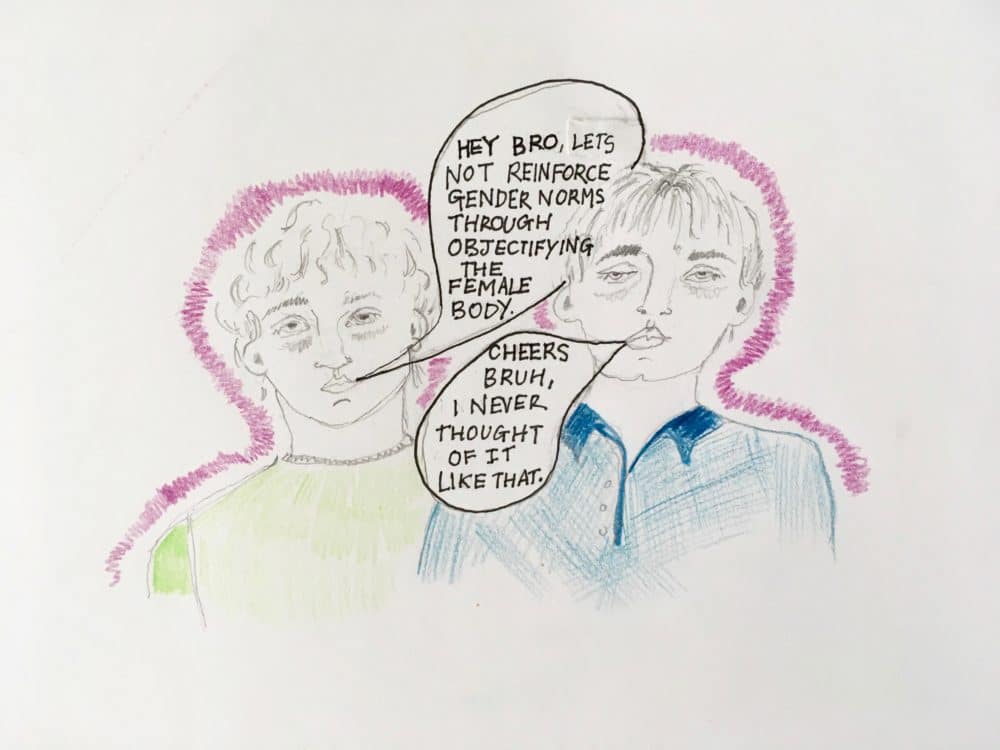

Unfortunately, since men who assault are unlikely to ever consider a woman’s experiences, we need men to start calling out other men. As long as some men continue to see the conquest of women as the quickest way to peer approval, and as long as other men refuse to challenge this norm, we will make no progress.

But if we can make this step — if we can make it so that to be masculine and powerful is to stand up for what’s right and not to take advantage of others — then we as men will no longer have to worry if the “right thing” to say to a man is the socially acceptable thing to say because the two will be equivalent.

I want to make this step. I want to change men. I want to change myself.

Zach Goodwin is a sophomore Diplomacy and World Affairs major. He can be reached at zgoodwin@oxy.edu.

![]()